The discovery of the unnecessary

Three centuries ago, risking life to climb a mountain would have been considered a madness, a useless and even harmful activity. The rationalism of the eighteenth century despised the wild environment of the mountains, the cliffs, the icy lands, the desolation and the dangers. Unsettling and unnecessary places, which today meekly allow the humans to stare at, tame and trivialize sometimes. Who are the figures who first climbed these peaks and get the Dolomites to be known worldwide? Here are four of them. We want to introduce them one by one.

John Ball

The Irish John Ball (1818-1889) conquered the mount Pelmo (3,168 mt.) on 19th September 1857. Ball had already climbed the Mont Blanc, visited the Moroccan Atlas Mountains and tried to climb the mount Cervino. During the climb to Pelmo he was accompanied by Giovan Battista Giacìn, his guide, who about thirty metres below the top discouraged him to go farther. Ball turned a deaf ear and reached the top where he could admire the view overlooking Grossglockner, Otztal Alps and the whole Dolomites. His glory perpetuates throughout the centuries.

Douglas William Freshfield

Douglas William Freshfield (1845-1934) is one of the greatest exponents of the British mountaineering. Freshfield gave a huge contribution to the discovery of the Dolomites, not only by undertaking lots of climbs, but also by fostering this sport as president of the famous British Alpine Club and as president of the Royal Geographical Society .

Paul Grohmann

Star of eight notable adventures in Monti Pallidi, Paul Grohmann (1838-1908) from Vienna is the climber who, according to the historian Antonio Berti, “opens with both hands the gates of the history of mountaineering in these divine mountains of ours”.

Georg Winkler

The German Georg Winkler (1869-1888) inaugurates the “climbing sport” era. Winkler, a not very tall man, almost silently reached the Dolomites in 1886 wearing his canvas sailing boots with hemp soles, not the ordinary hobnailed boots. He used to bring a hook that he launched hanging to a 12-metre-long rope. In 1887 he made his masterpiece as he climbed for the first time the southernmost tower of Vajolet.

English and Austrian mountaineers first climbed the Dolomites, whose territory was mostly under the Austrian empire in the nineteenth century. Soon, great mountain guides from Cortina, San Martino di Castrozza, Fassa, Val Gardena began to stand out. These four protagonists made history – or even “legend”.

Angelo Dibona (1879-1956) has his bronze bust in Cortina, created by the sculptor Augusto Murer. He also has a commemorative plaque where he is remembered as the “icon of the mountain guides of Ampezzo”. His greatest work was his climb along the south-west perpendicular wall on Croz of Altissimo in 1910.

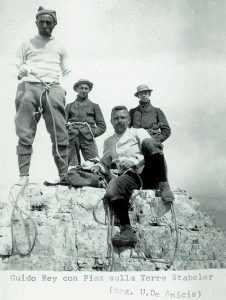

Tita Piaz

Giovanni Battista Piaz (1879-1948) called Tita, very famous mountain guide of Val di Fassa, is known as the “devil of the Dolomites” for his diabolic climbing ability. His realm is Vajolet mountain hut, built under the famous Torri, in the heart of Catinaccio.

Paula Wiesinger

The most winning climber of the Thirties in the Dolomites is Paula Wiesinger (1907-2001). From Bavaria, she moved to Val Gardena and became the climbing partner and wife of Hans Steger, a valiant mountaineer. Their union turned out to be important in the tourist reception in Val Gardena.

Giovan Battista Vinatzer

When he was only twenty-two, Giovan Battista Vinatzer (1912-1993) from Val Gardena, became of the best mountaineers of the world. On 8th August 1932, supported by his “young unconsciousness”, he opened the direct route from the ledge of Dulfer to the top of the friable Furchetta. But his golden year was 1936: on the south wall of Marmolada, Vinatzer climbed for 27 hours with Ettore Castiglioni. In the following twenty years, no one did better.

Evolution towards the grade VI and VII

Throughout the evolution of the mountaineering, and not only in the Dolomites, they very often thought they had reached the uttermost climbing limit. Then they always succeeded in pushing it over and over. Robert Hans Schmitt, standard bearer of the mountaineers of Vienna, after having climbed the chimney bearing his name at Punta delle Cinque Dita in 1890, stated “This climb is the hardest I have ever done. Who will go more?” He had just inaugurated the grade IV! In the same period, the legendary Paul Preuss, from Austria, was in the Dolomites and he managed to move the mountaineering setting out from the principle that the artificial means – rock climbing hammers and pins – hadn’t to be used. When Emil Solleder climbed the mount Civetta from its north-west rock faces in 1925, the VI grade era was born. Anyway, the uppermost climbing limit, if it exists, lies far in the future. In his 1974’s book, Reinhold Messner theorizes the VII grade (The seventh grade. Most extreme climbing).

From the abuse of the pins to the new free climbing

Preuss and Messner

The latest frontier of the mountaineering is “free solo”, a solitary pinless and ropeless climbing. Is it an act of bravery? A crazy challenge to death? In 2002, the German Alexander Huber climbed solo the classic via Hasse Brandler on the north wall of Cima Grande of Lavaredo.

Preuss was convinced that the rock didn’t have to be violated with the use or the abuse of pins. As you know, this thesis was contested by the eminent Tita Piaz, who did use pins. On the one hand the greatest risk, on the other hand (almost) the contrary. But it is likely that the overuse of protection has reduced the fascinating essence of this sport and it has also opened the gates to the highly equipped routes you can blithely climb at 8,000 meters. Then it has inexorably promoted a growing sport and consumer approach. Messner is the only one who can dislike this deviation from the pure mountaineering because he, before becoming the king of the highest peaks of the world, put himself in the spotlight as the “free climbing” and seventh grade promoter – he broke down the sixth grade barrier with flash repetitions on very dreaded vias.

Mountaineering today. The extreme and the speed

If you wonder about today’s climbing protagonists, we should mention Ueli Steck, the Swiss machine who died on Mount Everest on 30th April 2017. He broke many astonishing speed records on the infamous Eiger north wall. We also mention the friendly Alex Honnold, who always looks thoughtful and uninterested in his Youtube videos while he climbs as agile as a lizard on very smooth plates over frightful abysses – not good for your dizziness. Basically, nowadays everyone wants to be the best, the fastest, the bravest or the most athletic climber. For this reason, their safety moves to the background but consequences do come out when the mantle of snow gets unstable, due to the temperature inversions, making the icefalls, that the Sunday crowds love to assail, more fragile.

Writed from Roberto Serafin