Erri De Luca: using both hands… in the life and on the rocks

Today, from the top the Dolomiteslook like an archipelago of lands above the sea level.

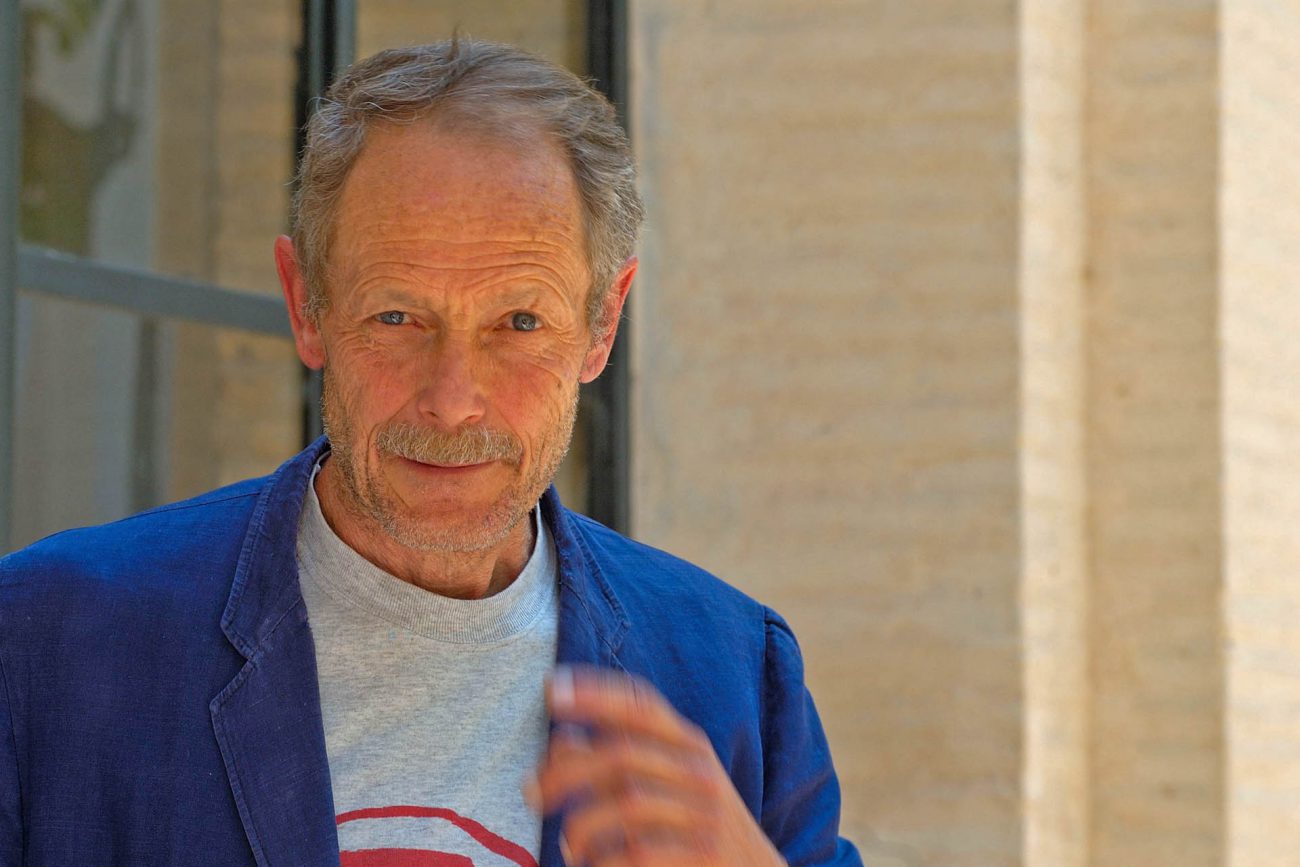

Erri De Luca was born in Neaples, in 1950. His several books have been translated into more than 30 languages. He wrote narrative books and pieces for the theatre and the cinema (he won a price at the Tribeca Film Festival of New York in 2013 for his piece “Il Turno di Notte lo fanno le Stelle”). Autodidact of Swahili, Russian, Yiddish and Ancient Hebrew, he translated literally some parts of the Old Testament. Among his woks: Arcobaleno (1992), Montedidio (2001), In nome della madre (2006), Il peso della farfalla (2009), published by Feltrinelli. In 2003, he has been accused of “incitation to commit an offence”, because he supported the protests against the building of the high-speed railway in Piedmont. In October 2015, the process finished and he was absolved. On this topic, he wrote the book La parola contraria. He loves hiking and the Dolomites are his favourite destination.

Internationally known writer and mountaineer. Involved in the defence of the rights of people and of the environment. A complicated and compelling life, as we can read in your several books. You supported the cause of the freedom of speech and several people supported you: the President of the French Republic François Hollande, the directors Jacques Audiard, Costa-Gravas and Wim Wenders, the singer Fiorella Mannoia and the climatologist Luca Mercalli.

Which events lead you to this uphill life?

I do not think I am conducting an uphill life; I am just supporting people who want to safeguard their health and the health of the territory they live in. Even the name High- Speed Railway is not right, because the train will take one only one hour less than the actual train. Furthermore, the train is not even going to stop directly in the city of Lyon, but 30 Km far away from it; this means, the passengers will have to reach the city centre by bus or by taxi. And the actual train is always empty! Since 20 years there have been protests, many citizens have been supporting the cause, and I am among them. I protested with them in the streets. I have been accused of committing an offense, but nobody left me alone, and everybody now knows better the territory of Susa Valley, in Piedmont. The process lasted two years, but it helped.

Because of your involvement in politics, you have been accused of criminal solicitation, and you have been compared to the supporters of terrorism. And you have been absolved. After the trial, you wrote the book La parola contraria1, whose summary we can find in the Moshlè way of saying 31,8 «Ptàkh pìkha le illèm»: speak in the name of the mute. Does a writer have to do this?

Defending the freedom of speech, against the willing of censorship and of defamation: this is what a person who works with words has to do. Speaking in the name of the person, who is not heard, of the mute, of the illiterate, of the prisoner, of the foreigner, who cannot speak Italian. Who is heard, has to do this job.

1 The opposite word

In the Dolomites, you have found a sport field of excellence. Why do you have this important bond to these rocks?

The beauty, their marine origin, because of which they are composed of coral, mother-of-pearl, skeleton of crustaceans. This is the reason why I climb in the Dolomites: the ages of the Earth, the big push through which they has been pushed up from the bottom of the sea. I love the limestone, which changes according to the hours of the day and the motion of the wind. I like climbing the ways that existed even before I was born, putting the hands on the handholds of the people who climbed before me. I climb in the summer, because I can touch the rocks with bare hands, from my surface to their surface.

Memory, nostalgia and emotion emerge from your books set in the mountains: Il peso della farfalla2, Sulla traccia di Nives3… Are there similarities between climbing and your way of writing?

Climbing means fumbling along a way, letting the hands finding the way, while the body follows. When you reach the top, you have to go back again. Writing means following that way, until the last syllable, which is not the reached top, but the bottom of the bottle.

In your opinion, can the Patronage of the UNESCO create a compromise between the safeguard and the development the international community should take as example?

The Unesco is a recognition, but a duty as well. In my opinion, through this recognition nothing is added to the celebrity of the landscape, but the duty to preserve it. The economy of the mountain has changed, and tourism is the most important source of earning. We have to be aware of the fact that the touristic offer on the Dolomites concerns the preservation of their beauty. I think people

are aware of this and respect the landscape. I believe in the intelligence of the tourists who are attracted by the beauty of the Dolomites, from Messner’s Museums to the bicycle races, during which the traffic is blocked.

Are expeditions still possible on the Dolomites? If yes, how?

There are few pounded ways, and many possibilities to hike and climb far away from streets and paths. From the valleys, mountains look like barriers, but from inside they are big communication systems between the slopes. You can spend days meeting animals and not meeting any person. You can forget that you have to go back.

SOFIA BRIGADOI (Traduzione Sara Covelli)